Anatomy of the Squat: Let Thy Heels Hover!

For yoga practitioners, if your heels don't touch the floor in your Yoga Squat, you've likely been approached by more than one well-meaning teacher eager to roll a blanket and stick it under your heels. Maybe you've been told your ankles or hips will open up over time.

And it might be true – but what if you've been doing yoga for years, and nothing has changed? Here's the big news: the inability of the heels to stay on the ground often has nothing to do with tightness in your muscles or tendons, and instead might be a problem of physics and leverage, due to the laws of gravity and the architecture of the bones of your ankles and hips.

The Yoga Squat, also called Malasana, can be a wonderful pose for anybody, but the misunderstanding about foot and heel positioning is widespread. The confusion is reinforced in a Yoga Journal article about squatting, where Marla Apt tells readers to squat with their feet together and heels on the floor. “If you are tight in your hips, groins, calves, and Achilles tendons, your heels may not reach the floor,” she says. While her advice might be true for beginners, if you've done yoga for more than a year or two without improvement, you are most likely dealing with a different problem - one of compression, rather than tension.

Leslie Kaminoff explains the issue at hand as he investigates squat pose in his nicely illustrated book, Yoga Anatomy:

Leslie Kaminoff explains the issue at hand as he investigates squat pose in his nicely illustrated book, Yoga Anatomy:

"The inability to dorsiflex the ankle deeply enough to keep the heels on the floor can be due to shortness in the Achilles tendon; however, restriction can also be in the front of the ankle. A quick fix is available by using support under the heels, but it's important not to become too reliant on it, because it will prevent activation of the intrinsic muscles of the feet, which stabilizes the arches, allows deeper flexion in the ankle, and aligns the bones of the foot and knee joint."

In other words: it's the bones that are stopping you, and that's okay. Squat, and let thy heels hover. I found the holy grail on this issue when Paul Grilley came to my studio for a yoga anatomy workshop. Paul is well known for bringing light to the variations in human anatomy and how they affect yoga practitioners. Years of frustration melted away as I listened to Paul describe what he calls the Principle of Counterbalance, which states that the real problem is one of balance and leverage.

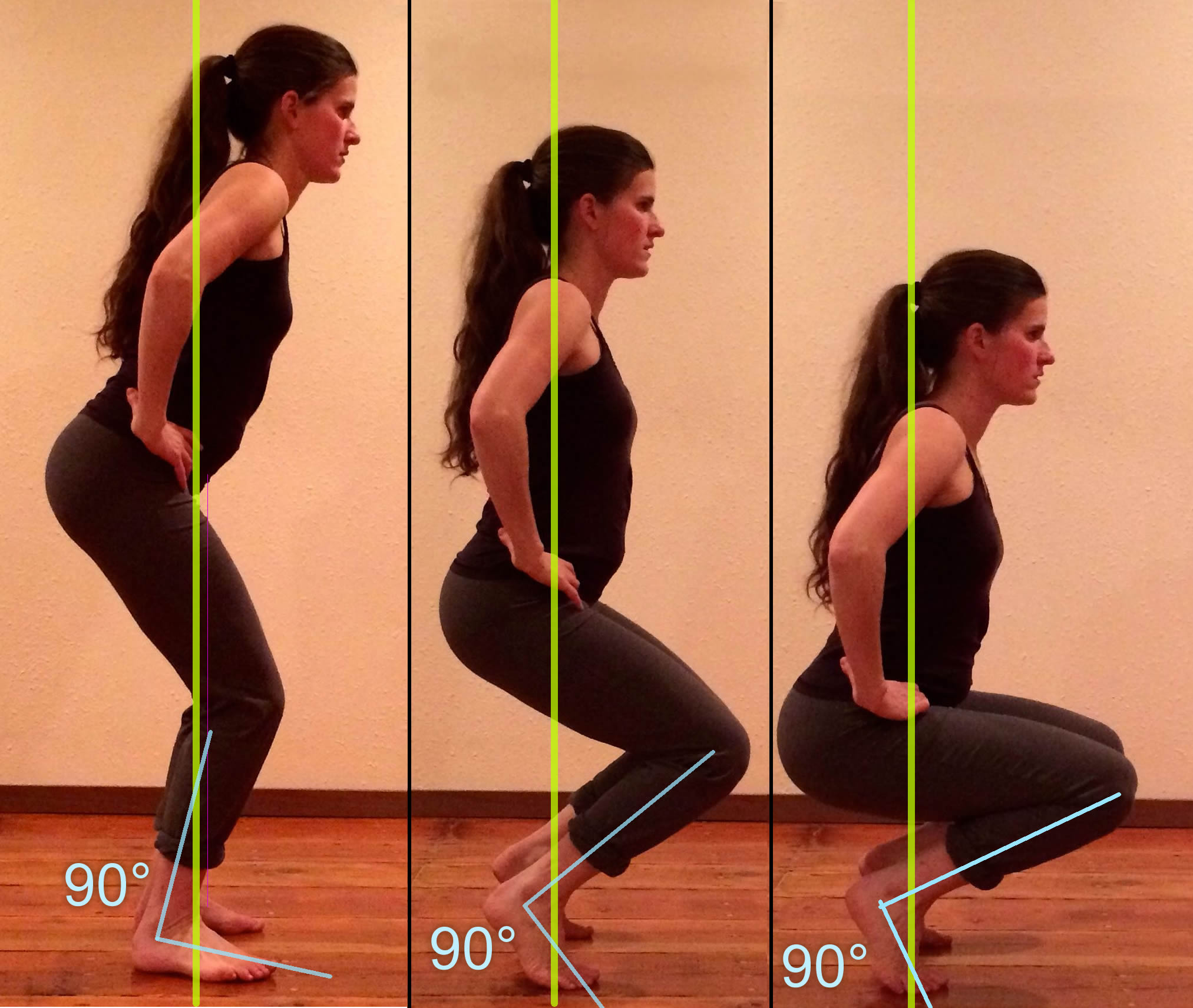

Devi's descent from Utkatasana to Squat. The green plumb lines show my center of gravity.

LEFT: Leaning my torso forward and turning my toes out slightly, I can bend just this much; however, I'm seriously stuck here.

MIDDLE: Lifting my heels up partially, I can begin to descend.

RIGHT: Lifting my heels farther, I can approach a squat. Notice my ankles are compressed at the same 90 degree angle through every phase of this. My restriction happens to be just under 90 degrees, but it's different for everyone.

I've been doing yoga for 23 years, and my ankles have never made it past the 90 degrees shown. Despite this restriction, I LOVE to squat - it feels great in my spine and hips, and there's absolutely nothing wrong with lifting my heels to make the pose possible.

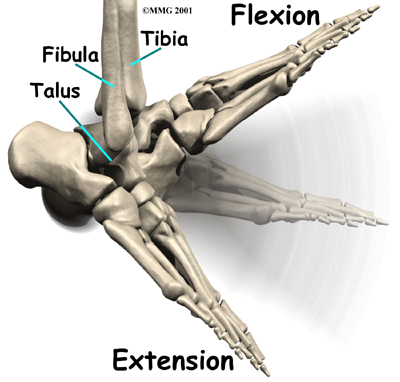

In squat, the ankles can only bend until the bottom of the shin bone (the tibia) collides with the topmost foot bone (the talus). This happens at a different angle in different people. Once this bony collision happens, the ankle stops bending. At this point, we're unable to bend our knees any farther because of the inability to balance upright – unless the heels are allowed to lift from the ground.

If the yogi is trying to force the heels to stay down, the knees will never bend, and the booty will never go back. The yogi will intuitively want to lean his upper body forward to counteract the danger of falling backward. At this point, our fine subject is probably doing some incorrect-looking version of chair pose (utkatasana) - not quite far enough to even be called a squat yet. Since she's probably being told by a teacher that her heels must stay down, she's stuck here. Most teachers will incorrectly diagnose this problem as tight hips or knees.

Lift the heels, and magic can happen – with the foot bones no longer stopping you, the knees can bend farther forward, enabling the hips to go back, and suddenly the yogi can squat.

Based on observing students in my classes for over 20 years, I'd estimate that about half of us have ankle limitations that compromise our squats and other postures. The student will not feel a strong stretch in the Achilles tendon but will feel certain that their ankles have gone as far as they’re willing to go. The term for this bone-on-bone limitation is called compression.

Compression occurs in all joints - it’s the reason some people can do splits and others will never be able to. It's the reason young elite ballet dancers get X-rayed during adolescence to determine if they have the hip bones to continue achieving feats of extraordinary range of motion. Compression determines the range of motion in most joints and varies from one person to the next.

I’ve done yoga with limited ankles for years. Before I understood what was limiting me, the standard malasana squat pose was on my Most Hated Poses list. But now that I've seen the light days, I absolutely love to squat – in my own way.

SQUAT VARIATIONS

Variation #3: Goddess Squat

Variation #4: Wall Squat

Variation #5: Hover Squat

For practical purposes, that is my go-to squat. Since my squats often happen as part of a flowing sequence, I rarely take the time to add a prop or move to the wall. This variation stretches all the same regions as the heels-down pose: the lower back, the knees, the hips, the Achilles tendons and the soles of the feet.

Other postures affected by ankle compression

Utkatasana, also known as Awkward Pose or Chair Pose. Awkward, indeed!

In the pose shown, this is as far as I can squat without lifting my heels from the ground. Seriously, I'm not exaggerating. My toes are even trying to creep outward and I'm straining to stop them. The dumb expression on my face reveals how pointless this pose feels to me. And where do I feel it? Is there a stretch in my hamstrings? Hips? Knees? Am I just stupid? Perhaps, but I know one thing - I feel this pose entirely in my feet and in my ankles, which hardly budge because of bone-on-bone compression. This prevents my knees from going any farther forward, which in turn makes it impossible to bend at the hips more without the weight of my torso causing me to fall backward (the Principle of Counterbalance).

Downward Dog

You've heard it before: "With enough practice, your heels will touch the ground." Twenty years of yoga, and I'm still counting. It has nothing to do with tight hamstrings or calves. Let thy heels hover.

Revolved triangle and revolved side-angle

If you force the heel of your back foot to stay on the ground in the standard alignment, there are two things that restricted ankles might cause: 1) The toes of your back foot will go more sideways than forward, and 90% of your teachers will try to correct this. After 6-12 months of this, your teachers may gently begin to wonder if you have poor hearing or learning problems. 2) The twist in the upper body will also be harder for you, because your back leg is forced into external rotation, which locks the hips, pelvis and lower spine away from the direction of the twist. There will be more demand on the middle and upper back to twist enough to achieve popular arm positions. Good luck with that! Or, if you just allow your back heel to lift... the kingdom of parivrtti is yours. Put it down when the teacher walks by.

Why this is important

Beating yourself up about your inability to do a certain posture is not what yoga is about. The Art of Yoga involves getting to know your body, learning to appreciate its abilities *and* honoring its limitations. Most experienced yogis reach a point at which they’ve been doing yoga for a few years, and the same problem persists in a certain posture with no improvement. At this point, it often means tightness in your muscles is not causing the problem - instead, you're fighting with your own skeletal structure.

As someone with many such bodily quirks, about five years into my yoga practice, I began to learn that my yoga teachers often didn’t know nearly as much as I did about my own body. I was ready to quit yoga numerous times, tired of the infuriating, misinformed "universal" alignment instructions that pervade yoga culture. But in many ways, this was where my yoga - and my best teaching - began. My own practice has evolved that is unlike anybody else's - a practice that is uniquely suited to my own body. My teaching has matured as I've learned to accept the fact that I can't really know what a student is feeling, and that their wild and weird variations could very well be an expression of a highly evolved, or deeply intuitive, sense of their own body.

So how to squat? How to teach it? I don't know. Can I tell by looking at a squat-challenged student if the problem is their ankles, knees or hips? No, I can't. What's important to know is that yoga teachers can do a great service to their ankle-challenged students if we cultivate alignment language that is less concerned with how the feet look, and more concerned with what we want students to feel, whether it's to stretch the low back and hips, to fire-up the quads, or something else.

Novice squatters are encouraged to find their own functional variations of foot positioning so they can enjoy this wonderful position without feelings of frustration and incompetence. If you come up with anything I haven't mentioned, drop me a note or send me a picture!